Panhandle Piloting: 3,000 Miles in a Mooney Mite (Part 1)

by Graham Shea

Quincy, CA

July, 2006

July heat baked the tarmac, which responded with rippling mirages. In the hangar, I dug into the small space behind the seat of the Mooney Mite to swap out a battery I figured wouldn't hold a charge anymore. That was exactly how I felt—drained of emotional energy and unable to pull any back into myself. Less than six months earlier I had watched my dad’s coffin go down slowly into the ground. The following afternoon my grandmother, his mom, died of a heart attack. In less than a month, and just as unexpectedly, I would lose my other grandmother too. The attention had been hard. I was grieving, but no longer in the way that anyone could understand. I probably looked normal, perhaps even happy at times. Every condolence came with the expectation I would show some appropriate emotion, a sign of comfort, appreciation, or some indicator of “how I was doing." It was well-intended, but exhausting.

Silence was what I needed. Space. The desert. That was where we used to go in the summers, Dad and I. When I was little I used to lie in the shade under his glider wing and smell the sagebrush. I was free to just be. The only sound was the wind, or the occasional radio check on the ramp. I’d sit in the cockpit of his glider while he rolled it out to the runway lineup for the day’s race.

By the time I was 16 I knew the sky over Quincy like my own driveway, and the Mite and I had become good friends. Girls fall in love with a pony, guys get a crush on a car. I had a little plane of my very own to explore the thousands of small airports all over the west. Dad called it a motorcycle of the sky. A Mite only has one seat. It would go a hundred miles, on three gallons of gas, in one hour. With full tanks, I could fly longer than I could sit in its hard seat. I remember Dad and I flying wing-to-wing, chatting over the radio about thermals to catch or coyotes to chase.

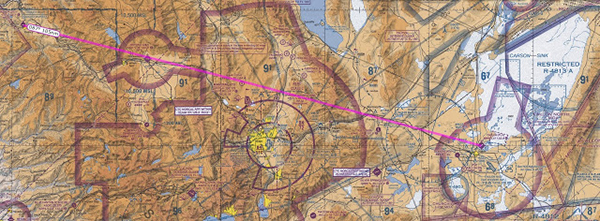

That evening we went up to the lake to watch the Fourth of July fireworks like we did every year. It didn't feel the same. The next morning I stuffed my backpack with a sleeping bag, camp stove, and a few books. I also grabbed my backpacker mandolin, which would just barely fit behind the seat with the backpack. There were a few other things I had to do, not knowing when I’d be back, so it was mid afternoon by the time I made it back out to the airport. I ran my hand over the nimble wings and tail, giving it a good preflight. Maybe I would go to Denver. I’d heard good things about Colorado. The prop sputtered into a windy hum with an easy flick of my hand on its metal edge, then I climbed in. My flight briefer said there were thunderstorms past Fallon, so I figured I’d put down there for the night and get an early start the next morning. The plane floated off the runway like a boat lifted by the tide. There were plenty of strong thermals in the hot afternoon, so I let them carry us up to 9,500’ and watched Quincy disappear below.

There were a few other things I had to do, not knowing when I’d be back, so it was mid afternoon by the time I made it back out to the airport. I ran my hand over the nimble wings and tail, giving it a good preflight. Maybe I would go to Denver. I’d heard good things about Colorado. The prop sputtered into a windy hum with an easy flick of my hand on its metal edge, then I climbed in. My flight briefer said there were thunderstorms past Fallon, so I figured I’d put down there for the night and get an early start the next morning. The plane floated off the runway like a boat lifted by the tide. There were plenty of strong thermals in the hot afternoon, so I let them carry us up to 9,500’ and watched Quincy disappear below.

Fallon’s Unicom was silent, and the airport seemed empty as I eased the throttle back and let the Mite sink down over top. A line of big thunderclouds stretched from north to south beyond the airport, and underneath them a curtain of gray rain veiled the hills on the horizon, decorating them with a hazy desert rainbow. The FBO walls and ceiling were covered with shirt tails, cut off of new pilots and marked with the date of the their first solo flight. Dad had mine framed, and I hung it in my room.

The man who ran the place filled up my tank and then drove me into town so I could get some soup and oatmeal for the trip. Back at the airport I found a nice spot in the sagebrush by the runway to lie back and enjoy the last of the evening light. The gentlest breeze breathed warmly through the brush. I pulled out the mandolin and played something absent-mindedly, my bare feet on the sand. As the sky turned pink, occasional jackrabbits loped through the pastel browns and greens around me. I was glad not to have any particular plans. It wasn't the kind of adventure you could plan, I thought to myself. It was the kind you just had to discover.

As the sunset bled down into the western horizon, the sand grew cool underneath my back. The stars overhead seemed to drift across the sky like satellites, though it was the thin veil of cloud underneath them that created the illusion of motion.

I set my alarm for 5:00 but woke up on my own at 4:45. The air was barely cool, almost that same perfect temperature that lulled me to sleep. I slipped out of my sleeping bag and stole barefoot across the sand further into the open to where I could watch the distant clouds begin to glow with the first full day of my journey.

The Mite sat with full tanks ready to go astride the runway. After washing up at the FBO (fixed base operator) and making myself some oatmeal with a portable water heater, I spread my maps out on the wing and tried to figure out how I was going to get to Eureka. Miles and miles of restricted airspace encircle Fallon from the north, south, and east like a giant crescent. I was able to get a hold of someone on the phone who said they didn't really activate those restricted areas until 8:00, so I was lucky I still had time to get through.

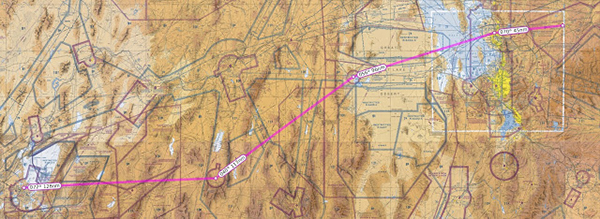

The sun just began to beam brightly when I took off, and all of Nevada sprawled out beneath me. That flight reminded me how wonderfully vast our country is. It seems so small now that we can hop on an airliner and end up on the other side in just a few hours. Miles below, there is so much we miss. But I saw everything, even wild herds of horses grazing in meadows surrounded by forest on top of mountains thousands and thousands of feet high. I was cruising at 9,500 feet, and they were not far below me. There is still all the adventure and discovery and wonder a soul can hope to find.

At Eureka an older man topped off my tanks. He said he remembered seeing my Mite a very long time ago in Reno. That’s how it is when you own a Mite. They have their own social lives, and they make friends even when you’re not around. I asked him for some advice on getting to Denver. I was 22, and though I’d grown up flying in the Sierra Nevadas, crossing the Rockies was a whole different ballgame. He recommended going up north through Salt Lake, so took his advice.

After climbing out of Eureka into a smooth, quiet sky I plugged my headset into my MP3 player and started listening to an audio book I’d brought called At the Back of the North Wind. In the book, the north wind comes and whispers through a crack to a boy who sleeps in the hay loft of his family’s stable. He opens the window, and night after night she takes him on her back to fly over the cities and oceans of the world. The author paints the sights and sensations in vivid detail. The book was written by George MacDonald in 1871, 25 years before the Wright brothers even began dabbling with unmanned gliders. I found myself choked up as the narrator described uncannily exactly what I was feeling and thinking as I myself rode the wind over mountains and valleys and little towns. Someone knew just what it would be like before anyone had ever seen an airplane fly.

Wendover made for a nice stop half way. Having never been there before, the WWII museum offered a fascinating couple hours’ break from the flying, and quite a contrast from where my mind had been during the previous flight. The Wendover Air Force base was where the B-29 unit trained that dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Another hour and I was in Ogden, where I had a late lunch at the airport café. Avgas there in 2006 was $3.90 a gallon, which meant I was paying a few dollars an hour of flying, or about a dollar every 25 miles to see the country from an open cockpit with the wind in my hair (not including the price of oatmeal). I called 1-800-WXBRIEF to check the weather again and see how much farther I could go before the afternoon thunderstorms took their turn to rule the sky. It looked like I could squeeze in one more flight if it was short.

East of Ogden, a wall of mountains shot up to over 9,500 feet, so I had to meander up to the nearest pass and goad the Mite up and up to a safe altitude over the rugged mountain forest. The wide, low desert of Nevada and Utah were behind me. The rest of the journey to Denver would be high, rugged, and completely new to me.

I settled down for the evening at the small airport in Evanston, WY at 7,138’, about the altitude of the highest mountains around my hometown of Quincy. A muscular phalanx of thunderstorms shut off the way to the east. The guys at the FBO were really friendly and didn't mind me camping out there for the night.

Almost every small airport has an old dog with a name like “Radar” who hangs out on a large, battered couch. Evanston had two dogs, who both became very jealous of my attention when I arrived and began to rough each other up to see who could win the right. But the couch belonged to the biggest cat I’d ever seen, who solicited a good pat and then fell asleep with his enormous head on my lap.

I felt a little tired myself after a good five hours of flying. At first I wondered what I could possibly do for the rest of the afternoon, but remembered right away that that was the whole reason I had left. I needed time and space that didn't have to be filled, that could exist for their own sake and remind me that life, like the pages of the books in my backpack, has margins.

I lay out on the lawn for a few hours and read a book about the Arthurian knights who rode about the country sleeping in forests and glens looking for adventure and wrongs to put right. When the light faded, I wandered up to the top of the hill behind the airport. A deer startled and bounded out of the sagebrush, which was greener than Nevada’s. I heated up some clam chowder on my camp stove and drank in the view from my perch—nothing but freedom in all directions. The wide open space was full of birds singing. There’s a song Glen Phillips sings that says, “I've got a roof over my head, or sky if I choose.”

With the thunderstorms still rolling around, I zipped into my bivy sack and draped the poncho over my backpack rather than using it as a ground cloth. I woke up to rain falling and flashes of lightning. Suddenly being on top of the tallest hill around seemed like a dumb idea, but the storm wasn't quite bad enough to make me willing to get all wet by moving somewhere else. The bivy sack covered my face with only mesh, so I had to roll onto my stomach for the rest of the night to keep dry. The flashes of lightning lit up the darkness of my little cocoon through the fabric, but the rain rolled off into the sand.

2014-02-22