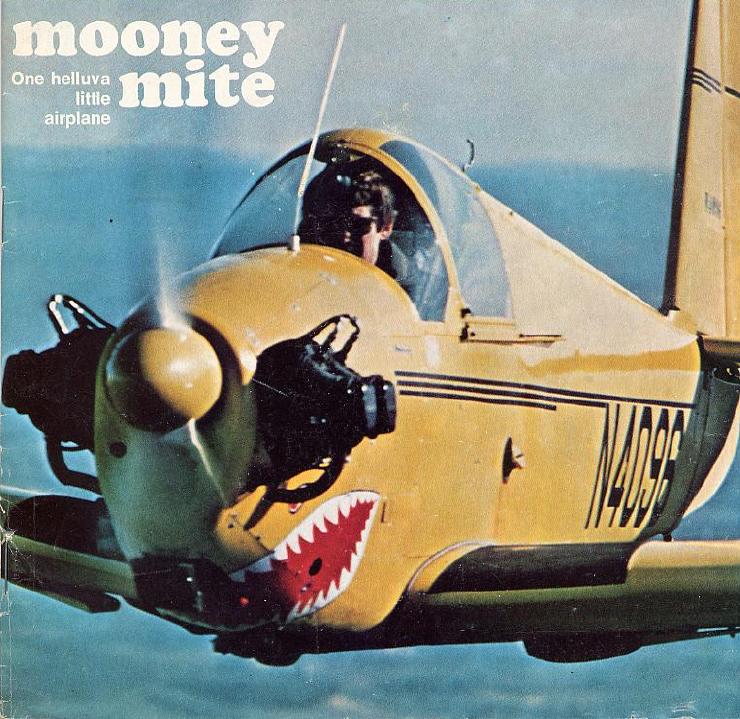

Mini Mooney by Budd Davisson

This was taken from Air Progress, March, 1976

"Aw come on," I could hear myself muttering. "This is ridiculous." I was sitting there, wedged into a tiny plywood cubby hole, bouncing upward through some low level turbulence as I fumbled around under my right knee with both hands trying to find an elusive slot in which the gear handle was supposed to magically snap. Wrong! Every time I'd get the handle close, I'd hit a bump, the airplane would lurch, I'd grab the stick. Then weight of the gear would overcome the dwindling strength in my trembling right arm and the lever would come back up, letting the gear hang part way out. I'd always wanted to fly a Mooney Mite, but as I watched the horizon tilting, my feet freezing, and my arm wilting, I wasn't so sure.

In all fairness, I have to say that my experience with the famous little plywood Messerschmitt from Texas was in anything but the most ideal of circumstances. The weather was cold as an editor's heart (Humbug!-ED.) and scattered sharp edged turbulence continuously poked and jabbed when you least expected it. Compounding this was the fact that I was wearing all the Salvation Army sweaters I could find, a flight suit and a ski jacket so, what was already a less than palatial cockpit assumed the relative proportions of a straitjacket.

In all fairness, I have to say that my experience with the famous little plywood Messerschmitt from Texas was in anything but the most ideal of circumstances. The weather was cold as an editor's heart (Humbug!-ED.) and scattered sharp edged turbulence continuously poked and jabbed when you least expected it. Compounding this was the fact that I was wearing all the Salvation Army sweaters I could find, a flight suit and a ski jacket so, what was already a less than palatial cockpit assumed the relative proportions of a straitjacket.

The Mooney Mite is the closest thing to a homebuilt to ever come out of the U.S. aircraft industry. It was built to satisfy that urge within us that says we should each have an aerial motorcycle that would give outstanding performance and gallantly fulfill our personal transportation needs. It would always be there, parked next to the Volkswagen in the carport, ready to trundle down the street to the adjacent runway and wing us towards a distant business meeting. Of course, that urge almost always dies when the dollar value of building the aforementioned carport next to a runway in a sunny clime is computed.

The Mite found its way off Al Mooney's talented design board and into our hearts in 1948 as part of the soon-to-burst postwar general aviation boom. As originally designed, it would use the Crosley auto engine, an incredibly tiny four cylinder tinker-toy that featured a single overhead cam, oven-brazed sheet metal block and 22 hp at 7000 rpm. That's right 22 hp! The M-18 not only flew with the engine, but it was fully certified and the first 12 production airplanes used it However, the economics of modifying the engine to aircraft specifications made the 65 hp Lycoming look like a much smarter installation. So, the sleek little nose was opened up and the familiar Lycoming or Continental jugs hanging out in the breeze became the standard snoot of the Mooney Mite. Since the airplane was designed for only 22 hp (it did 110 mph with that engine at 1.5 gallons per hour) the Lycomings and Continentals gave it nearly 65% reserve power, all of which was available to make it climb. It was quickly found that they had to use an extremely coarse pitch prop to keep takeoff and climb performance down, otherwise the nose angle during climb was so high they had problems with the gravity feed fuel system. This reserve power gave it astounding performance figures, including a 1500 fpm climb, service ceiling of 24,000 feet and an absolute ceiling of 27,000 feet. There's no doubt that the Mite is a Mooney. The forward canted, full-flying tail (which developed an annoying habit of falling off), the forward sweep of the wings and the knee action landing gear are pure Mooney. The airframe itself is a combination of wood and tubing construction. The wings use a plywood torsion box forward of the main spar with the remainder being fabric covered. The fuselage is steel tubing to the aft cockpit bulkhead and then wood monocoque back to the wood tail. The tail is hung out on a tubing truss and the whole thing swivels up and down for trimming.

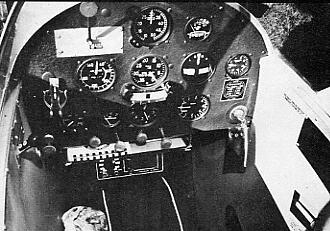

The trim is a unique system that incorporates the flaps as part of the trim cycle. There is a knob on the left side of the cockpit that changes the gearing on the trim from course to fine. When landing or taking off, it should be in the course position so turning the trim crank .produces major changes. If you crank the trim all the way back, the flaps come down and pitch changes are supposedly already trimmed out. It didn't work that way for me.

When I decided it was time for me to finally get my hands on a Mite, I started looking in the same place everybody else does . . . Trade-A-Plane. There were four Mites listed, and one had a New Jersey number not far from me. I got on the horn. When the owner answered, I started bending his ear about how I wanted to make his airplane famous and take a few pictures. The guy kept trying to butt in and finally said, "Hey, Budd. It's me, Fred Morris." I felt like a dummy. Not only is Freda friend of mine but he's always bought neat-o airplanes and I've always done pireps on them. Anyway, to make a short story long, we set a date, the day came and I took his airplane and went flying.

As mentioned earlier, I looked like an arthritic teddy bear as I tried to stuff my overbundled body into the Mite. With the canopy open the hole looked large enough, but once inside I had to do a little wiggling to get my legs under the dash. In retrospect, I would have been more comfortable with no back cushion because my knees protruded out from under the panel at an unwieldy angle (and I'm only 5'10"). My first impression was that I was in no way going to be able to fly this thing because my elbows were making irreparable indentations in my rib cage and the cockpit sides. Then Fred explained the landing gear operation and I knew for a fact that I was in real trouble.

The famous switchblade landing gear of the Mite is operated by a single lever on the right side of the cockpit. No, not where you're visualizing it, by your right hip, but clear down by your right foot. To reach the handle you have to change hands on the stick and lean way forward to get your right hand clear up to the firewall. The lever is sticking up from the .floor vertically, with its spring-loaded handle stuck into a socket. To unlock the gear; you grab the lever's grip, pull it down out of the socket and then pull the lever back towards you. The lever rotates 90 degrees, firewall to seat bottom, where the spring-loaded top is supposed to snap into a little ring to keep the gear up. It looked simple enough, except I noticed I couldn't see the up-lock ring without moving my right leg inboard which then restricted the stick movement.

Three quick shots of prime, mags on both, two blades and the Continental began doing its characteristic chug-chug-clatter routine. Fred had spent a lot of time telling me not to use the brakes so I had to plan my paths through the puddles and airplanes with great care. I noticed, as I passed beneath the wing of a 172, that there are lots of advantages to little airplanes on crowded ramps.

The turning radius without brakes is almost exactly as wide as a 50 ft. runway, but such a wide turn at the end of the runway gave me plenty of room to clear for traffic. I reached up for the throttle which is a black plastic peanut placed far enough forward on the left wall to bring your left elbow out from between your ribs. The neutral position of the stick does the same for your right arm. "Aha!" I thought, "Maybe I can fly this thing after all."

Thumb to throttle. Throttle to forward. The chugs got closer together, the noise got worse, the airplane gave a couple reluctant vibrations and began rolling forward. Inertia is the greatest enemy of 65 horse powerplants. Once rolling, however, it grabbed for speed fairly quickly and I don't remember doing anything at all to make it fly. It came off the ground in a nearly level attitude and probably would have climbed out all by itself with the nose only slightly above the horizon had I not given a gentle tug on the stick.

First problem: turn the trim system from coarse to fine. It was more trouble than it was worth to get it with my left hand, so I changed hands on the stick and reached across with my right hand for it. Voila! I discovered the secret to working in tight quarters . . . reach across so your arm has more room to work.

After I was three or four hundred feet up and trimmed for an 80 mph climb, I decided it was time to try for the gear. Jerk, tug, pull, stab! I finally got it in the slot. If I owned a Mite one of the first things I would do is make a "V" shaped guide that would mount on the up-lock slot on the floor. The lever on Fred's Mite wiggles sideways too much and a guide is needed to accurately force the lever into the slot with one hand. This is not the usual case with M-18's, I'm told.

Once I got the gear up and squared everything away, I suddenly found myself quite comfortable in an over-stuffed sort of way. Wearing lighter clothes would probably make the airplane seem a size or two larger and most of my problems would have disappeared. Even so, during climb-out I was already beginning to warm up to the airplane, though my feet were freezing (OAT 10° F).

I feel sorry for every pilot who flies his entire life without ever experiencing the thrill of a little airplane like the Mite, be it a homebuilt or otherwise. The controls fill your hand and your brain like three-dimensional random thoughts that need only be brought to mind to become reality. A bank is only a mental message away and the gorgeous feeling of flight is insulated only by your gloves. I took mine off. Despite my earlier doubts about the Mite, as a flying machine its emphasis is more on flying and less on machine, and I loved it if only for that reason.

Visibility is, as might be expected, nearly perfect, although the wing does block downward visibility somewhat. Even twisting around to see behind you is no big deal, which incidentally, is a good thing because the fuel gauge is a plastic tube that runs up the bulkhead right behind your noggin.

Eleven gallons are housed behind you (15 gallons on some) and an additional six are in an auxiliary tank that has to be wobble-pumped up to the main tank to be used. At 3.5 gallons an hour, that's an endurance of almost 5 hours. My two-way speed checks gave a speed of about 118 mph so the no reserve range of this little 65 hp number is a solid 590 miles. I've even heard of these things being set up for IFR and night work. Quite honestly, if I had the opportunity to do some cushion shifting I'd be happy to bore holes in the sky for 6 hours.

The stability is good for such a small package, especially through the pitch axis, although this particular airplane was a mite (pun intended) out of rig, as it always wanted to turn left. Control pressures were what you'd expect, light although not as light as most homebuilts, and the rudder gets useless in steep maneuvering. It seems everything named Mooney is short in the rudder department.

Stalls clean came around 55 mph with nothing spectacular happening. With flaps down, however, the Mite would slow down to 50 mph, shudder, try to drop its nose, and then, if you insisted on holding the stick back, it would really snap its nose towards the ground. It flies out of a stall immediately, but leaves no doubt when it's had enough. With the gear down, the break is a bit more civilized.

I practiced snapping the gear up and down several times and found things worked out best if I grabbed the handle with my thumb pointing down, giving it a healthy yank and letting the inertia of the gear legs help me out. Later Mites (officially called; are you ready for this: "Wee Scotsman" after 1953) have a shorter throw landing gear system, which should work even better.

After making a couple of fighter pilot passes on two Cherokees, a Baron and a chicken hawk, I started letting down to head for the barn. In the process, I found that power off and clean, you're lucky if you can persuade the Mite to descend at 400-500 fpm. Those high aspect ratio wings would probably work out well in slope soaring.

Fortunately, the stall series had shown me that Fred's airplane's trim system was wildly out of rig and would force me to carry bunches of forward stick with the flaps out. Otherwise, between trying to get the gear out and keep the nose down, I would have had an interesting trip around, the pattern. When properly rigged, the trim/flap system is supposed to work together so that the airplane is never out of trim.

Seventy to seventy-five mph felt good on final and the little bugger settled into the groove and held its speed like a 747 all the way to the runway. As we hit the downdraft for which my home field (Sussex, N.J.) is famous, I had to jab a little with the stick to keep the nose down. Otherwise, the only thing of note was the reluctance with which the airplane landed. It's a floater and any extra speed is going to embarrass the hell out of you. It lands a lot like a T-Craft except the nose-wheel makes it track straight as a die.

Now that I've had my chance at a Mite, I can see why they are such a popular item at the paltry $3000-4000 they currently go for. Mites also have another thing that makes them unique; you can buy the plans for them and build one yourself.

The M-18 Mite went out of production in 1955 and the type certificate was eventually sold to Fred Quarles of Mooney Mite Aircraft Corporation (Box 3999, Charlottsville, VA 22903) who now offers complete plans to anybody who thinks they'd like to build their own. So far over 500 people have. And at $70 each his plans are a bargain. His long term objective is to put a modified version of the airplane back into production. This one would use newer state-of-the-art tooling and an O-200 100 hp powerplant. That would give a solid 65 hp at around 10,000 feet which would be like having a turbo-charged Mite that could speed up to 175 mph at altitude. With that engine, it would climb like a frightened squirrel.

In total, there were 292 Mooney Mites built (285 according to some sources). There were four series in the production, of which 83 were L models with Lycoming engines and a 780 pound gross weight. Then 124 Cs and LAs were built with an increased gross of 850 pounds. The remainder were C-55s which were a little longer and had a slightly higher canopy, sort of a Malcolm hood, that messed up the lines slightly but made it easier for tall folks to look around. It's anybody's guess how many Mites still survive, but I personally know of two hanging in hangar rafters waiting for somebody to rebuild them. (Don't write, they aren't for sale.)

Around 1953 they cranked out one Mite that I'm certain was tagged Mighty Mite by any who saw it; would you believe a 90 hp engine, and two .30 caliber machine guns? Officially known as the M-19, this was Mooney's bid for a ground support, COIN airplane and although much similar in appearance to a M-18, it was a much modified airframe. It was beefed up in many areas, featured a wider cockpit and the engine was fully cowled. Imagine what a kick it would be taxiing up to the warbird line at your next fly-in and demanding to be parked next to a P-51!

Personally, I very much like the airplane, but I couldn't own one. Because of the way they fly and the thoughts they plant in your head, I'm afraid they'd wear down my will power and my enthusiasm would get the best of me. They aren't acrobatic in even the mildest sense of the word and I'd wind up spreading plywood all over three counties. But, for my money, they are a hell of a cute little airplane and the EPA should take note: a Mooney Mite gets better than 33 miles per gallon in both city and highway driving.

At the time of publishing, N4096, a 1952 M-18C, is owned by Winslow Jones of Glen Ellyn, IL.

August 3, 2001