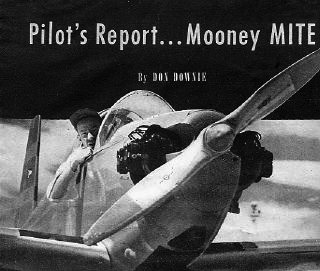

Pilot's Report...Mooney MITE

MOONEY single seater, with Pilot-Author Don Downie at controls is powered by a 65-hp Lycoming, and has a 27-foot wing span.

|

|

LOOK at that little devil go up!

If you see a trim little pint-sized pea-shooter take off almost without a roll and then climb to a thousand feet over the boundary of the airport, it's probably a late-model Mooney Mite.

PEASHOOTER, pint-sized that is, climbed to 12, 200 feet at full throttle in 14 minutes. Airspeed was held at 65, 70 mph. Final "test" landing was shot at McCarren Field, Las Vegas, during a private flying fiesta (below)

Originally powered with a 24-hp Crosley automobile engine, this one-placer was recently re-designed and licensed to handle a 65-hp Lycoming engine. Performance now is just about out of this world since the published absolute ceiling is over 25,000 feet.

COCKPIT photo of tiny Mooney Mite shows the gear-warning wig-wag on upper left of panel. Note flap lever on left.

COCKPIT photo of tiny Mooney Mite shows the gear-warning wig-wag on upper left of panel. Note flap lever on left.

Research flying for this SKYWAYS' pilot report was done during the annual "Holiday On Wings" at Las Vegas, Nevada. The 65-hp Mooney, N353A, was the first high-powered model to reach the Pacific Coast and the fourth to be completed at the factory in Wichita, Kan.

"Just how do you check out in a single-place airplane?" We asked George Bontempt, sales representative who flew the Mooney to Las Vegas for West Coast Distributor Harry Royster. "You just get in and fly it. Come on out to the ship and I'll show you how to get the landing gear up. After that, you're strictly on your own."

The morning was hot and the wind gusty as we walked around the Mooney at the Vegas Sky Corral. In general appearance, the Mooney looks much like the Culver PQ-14 radio-controlled target plane. Aft of the cockpit, the ship is constructed of a plywood monocoque cone. The wing has a wood spar with a leading edge covered with plywood. The tail surfaces are fabric and both rudder and elevators are hinged at their junction point with the fuselage. When you roll back on the trim-tab, the rudder, elevators and tail-cone all move. Shallow-depth flaps cover the whole trailing edge of the wing not devoted to ailerons. The flaps are operated by the trim-tab handle and come down only after the stabilizer is rolled all the way back. Mooney calls this system a "safe-trim" control set-up.

The forward section of the fuselage is built of welded tubing covered with fabric. The cockpit interior is conventional except for the nose-wheel well that humps up from the floor between the rudder pedals and the stick. The Mooney has toe brakes and a steerable nose-wheel.

The most unusual feature of this little air- plane, not counting its sensational rate of climb. is the neat manually-operated retractable landing gear. A long lever),, similar to the parking brake on a pre-war auto, is mounted on the far right side of the cockpit. In the "down" position, this handle locks forward into a slot just above the right rudder pedal. To retract the gear, the pilot merely leans forward, grabs the handle, pulls down on it to release it from the slot and then brings it back about 18 inches into another slot just to the right of the seat. That's all there is to it! No hydraulic pump or electric motor- just dependable pilot-power.

HANGAR APRON-MATE of the little Mooney single-seater was another and somewhat faster one-placer, the F-51 Mustang

Since the gear-retracting mechanism was the only unconventional fixture on the Mooney, we climbed into the cockpit from the leading edge of the wing and fired-up the engine. There is no starter and the ship is as difficult to crank as an Ercoupe because the prop hub is so low to the ground. Inside the cockpit there is plenty of room for a six-footer even though the only, adjustments in the seat are made by re-distributing the cushions.

UNITED MAINLINER at Las Vegas really made a midget of the Mooney. Ship's tires originally were for wheel barrows

LYCOMING engine, 65-hp, now powers the Mooney. First engine that powered the tiny ship was 24-hp Crosley motor

Visibility in taxiing is wonderful -- though it seems unusual to be sitting so close to the ground. Even with its small 400x4 tires, built originally for wheel-barrows and adapted to the Mooney to cut-down costs, the ship had no tendency to bog down on the sandy taxiways. Since the weight empty of the Mooney is only 500 pounds, our total take-off weight was roughly 725 pounds, including a full tank of 12 gallons of gas. The gas tank, incidentally, is mounted high in the fuselage -- Just aft of the pilot's head. No fuel pump is needed since gas will feed by gravity in any normal flight attitude.

The weather was hot enough -- about 90° on the ground so that no lengthy engine run-up was needed. After checking the mags with two toggle switches at the far right side of the cockpit, we tried the carburetor heat control directly below the tachometer. There would be little chance of carburetor icing here, but it is a long-established habit. The ship also has a cabin heater that was not used on this flight.

Even on this hot, sandy 2200-foot high airport, the Mooney hopped into the air in the length of a football field. Take-off is easy. There is little torque to worry about with the tricycle gear but we were cautioned by Mr. Bontempt not to "horse" the ship into the air before it really wanted to fly. The control touch in the air is almost identical with the old Culver Cadet. Only the slightest movement of the controls brings an instant response from the Mooney. You don't actually move the controls, you just think about it! After over-controlling the ailerons in the gusty air close to the ground, we let go our heavy-handed grip on the control stick and flew it with finger-tip pressures. Don't get the idea that the ship is "hot" or touchy to fly. It just handles easily with minimum stick pressures and qualifies well as a "lazy" pilot's airplane.

Getting the gear up is an interesting experiment. Since it was our first hop in this single-seater, we climbed at a conservative 70 mph until we had about 400 feet before reaching down for the hand-brake handle of the landing gear. It takes quite a little pressure to unlock the gear. However, once it is disengaged, the handle swings back easily until it is three or four inches short of the up-and-locked position. Then the pilot must apply considerable pressure to force the gear-handle back into the fully-retracted lock. A lightweight gal pilot might find considerable difficulty in locking this gear, but if the pilot has normal strength in his arms, the whole arrangement is very neat. There should be little or no maintenance on this one pilot-power retracting gear. It is, to this pilot's way of thinking, the fastest retracting gear yet put on an airplane once you "get the hang" of the lever control. In watching Mr. Bontempt fly the ship later for demonstrations, the pilot was able to get the gear up and locked within seconds after the Mooney broke ground.

Since the Mooney is noted for its high-climbing characteristics, we decided to see how long it would take to climb 10,000 feet. The Mooney is available with two different propellers, one pitched for fast take-off and rapid climb and the other for more efficient cruising speeds. N353A was fitted with a cruising prop, the air was hot and bumpy, so we didn't expect too much in the climb department.

With full throttle, it took exactly 14 minutes to climb from the 2200-foot-high Sky Corral to 12,200 feet. Airspeed was held between 65 and 70 mph.

The angle of climb of this little Mooney is so steep that visibility is partially restricted with the nose up in a full- throttle climb. We found it necessary to make a few shallow turns while going up to see what was out ahead of us. Later, we loosened the safety belt and doubled one of the cushions in the seat so that our head just cleared the hatch and visibility improved greatly.

A placard on the instrument panel says "Do not open hatch in flight above an IAS (Indicated Air Speed) of 109 mph." Since it was hot and stuffy on the ground, we cracked the hatch back one notch-about two inches- Just as soon as we settled down and began to feel at home in the little ship. This is the only source of fresh air in the Mooney.

At 10,000 feet above Las Vegas, the blue water of nearby Lake Mead stands out in the sharpest contrast against the sand-and-sagebrush of the desert. Bright green lawns of the swank resort hotels dot the main highway west of town and you can see for 50 miles in any direction through the clear desert air.

No attempt has been made to muffle the Lycoming engine and the little ship is quite noisy with the hatch partially- opened. This was the only time during our stay in Las Vegas that it was not possible to hear the hungry tinkle of Nevada's endless slot machines.

After checking the 10,000-foot climb of the Mooney, we had plenty of altitude to try out the stalling characteristics. At the top of our climb we pulled back on the stick with full throttle until the ship shuddered and stalled. The indicated airspeed was 40 mph. There is plenty of warning by stick buffeting before the Mooney stalls and the pay-off is not at all violent.

With gear and flaps down, the stall is slightly more abrupt but not at all vicious. High-speed .stalls out of turns with excessive back stick give the same ample "warning. First you feel the vibration of the stall through your fingers on the stick. Then, as it becomes more pronounced, the whole airplane buffets. We tried to force the little ship off into a spin and found that it took full back stick and full rudder to make it pay off. The slightest relaxation of back pressure puts the Mooney right back flying again. Without a parachute, these spin tests were restricted merely to a spin entry followed by an immediate pull-out.

Small triangular stall strips near the fuselage help make the root of the wing stall first so that the ship has full aileron control down to its slowest flying speed.

Either the airspeed was slow on N353A or we didn't have the mixture control leaned out properly for full power. In level flight with full throttle, we were able to indicate only 93 mph at 12,200 feet. That calibrates out roughly at 115 mph. Since there are no mile-apart section lines near Las Vegas, we were unable to make an accurate check. Flown by a pilot completely familiar with the Mooney, the performance would undoubtedly have been better. I've had it on good authority that the Mooney whips along at a nice 115 mph at half throttle. Mr. Bontempt advised us that he flew this same plane to Las Vegas from Clover Field in Santa Monica in loose formation with a loaded Stinson flown at cruising power.

Since it was cool and comfortable at higher altitudes, we stayed at 10,000 feet and did a series of steep "Lazy 8's" to get the feel of the airplane. The airspeed on this maneuver ranged from 40 to 110 mph. Nose down, the Mooney's clean design makes it pick up speed very rapidly. Yet it handles smoothly with plenty of control remaining at the minimum speed on top of the "8."

This flying high and on your own is really quite a novelty. With the exception of military pursuit pilots, very few flyers have logged any time in single-seat equipment. There are absolutely no distractions; no instructor to ask questions of, no passengers with whom to jabber and no radio to talk over. This lonesome feeling gives a pilot that seldom-realized opportunity to grasp that vastness and magnitude of the sky that each student feels when he first solos.

Reluctantly we let-down into the hot, bumpy layer of air that hovered over Las Vegas. We circled the town and decided to shoot a landing at the Sky Haven Airport northwest of town. Their 4800-foot runway is merely a strip graded out of the desert and soft spots were in evidence from a recent rain.

As we circled the airport, a popular four-placer took off. With the soft runway and the hot midday air, the ship took a very long roll before breaking ground. But it was not so with the Mooney.

We found that the easiest way to lower the landing gear was to slow the ship up to about 70 mph, unlock the landing gear lever and let the gear fall to a half-way down position. Here the wind against the nose-wheel seems to stop the gear. On our first try, we high-pressured the landing gear handle into the down-and-locked position with our right hand and took some skin off our wrist. The next try was made by dropping the gear into this "floating" mid-point position and then standing on the "brake" handle with our right foot. Pressure is easier to apply this way and the little ship flies perfectly well without touching the rudder pedals.

The Mooney has one of the neatest little gadgets to check the landing gear for down-and-locked that has yet been put on an airplane. You can't see either the nose wheel or the main gear from the cockpit, so some sort of a warning gadget must be used to remind the pilot in case he's forgotten to drop his gear.

The Mooney uses a little red dot, about the size of a 50-cent piece, on the end of a six-inch rod. If the gear is not down and locked, this gadget wig-wags like a child's metronome as the throttle is brought back beyond 1200 or 1400 rpm's. The gadget is driven directly from the intake manifold, just like a vacuum windshield wiper on a car. There are no electrical contacts, no red lights or buzzers to burn out. When the engine output is cut below 1200 rpm, the wig-wag goes into action. While a pilot might miss the noise of a horn or the blink of a light, it would be mighty difficult for him to ignore a red-dot flopping back and forth in front of his face.

As in any strange airplane, we came in on the fast side for our initial landing. The airspeed held an indicated 70 mph as we crossed the fence and eased down close to the ground. Then we floated . . . and floated . . . as we kept the little airplane in the air as long as possible. With the stick all the way back, she quit flying at 45 mph and barely touched the stub of a tail-skid in the sand as we landed.

The little wheel-barrow tire didn't dig into the sand even though we used full brake and skidded the main wheels. The Mooney ground to a stop in less than 250 feet.

The Mooney does not turn as short a circle on the ground as many tricycle-geared planes so you must plan ahead a little while taxiing.

By now it was so hot on the ground that we opened the hatch all the way and left it there. Since there was no one available to ask whether or not you flew the Mooney with the hatch fully opened, we ran up the engine and decided to try it.

Our take-off roll from the Sky Haven took up less than half the runway used by the previous four-placer. We hopped the little ship off the ground and had the gear tucked away before we were over the end of the runway.

With the hatch open, the Mooney is naturally quite windy. All the dust and dirt that had accumulated while the ship was tied down the night before floated up around our eyes and out of the cockpit. There seemed to be no bad-handling characteristics with the hatch open and the landing speeds were unchanged. With the short exhaust stacks barking less than three feet from your left ear, however, it was quite noisy.

There is a forward suction around the canopy in flight. When we experimented with closing the hatch in flight, it picked up speed as it moved forward and slammed rather hard into the windshield stops.

Since we had been in the air nearly an hour, we looked back at the visual gas gauge. We had burned less than three gallons of gas!

We flew around town lazily and shot a couple of more landings at the Sky Corral before making a final landing at the airline terminal, McCarren Field. We flew a square-cornered traffic pattern, dropped the gear on the downwind leg and finally picked up a green light from the tower as the little Mooney rolled out on its base leg. Without even a radio receiver, flying into an airline terminal can be a little difficult. N353A had been released from the factory licensed only for daylight flights and was equipped neither with generator nor lights. Testing is now underway at the factory for an inexpensive belt-driven generator. Everything on the Mooney, with the exception of the engine, propeller, instruments and tires, is made at the Mooney factory in Wichita, Kansas.

While taxiing in from the huge runway at McCarren Field, we passed actor Jimmy Stewart's "Thunderbird," the souped-up F-51 that is the current transcontinental record holder. The racer had been flown in for display purposes by pilot Joe De-Bona.

Actually, the F-51 and the Mooney have in a good many things in common-though speed is not one of them. They both have plenty of power for the size of the airplane. Both carry only a pilot and very little else. Both are full-cantilever, low-winged ships with retractable gear and both climb like an Angel late for a date.

One interesting side-light on the Mooney is the method of checking out pilots in it. Prominently displayed on the bulletin board Harry Royster's office at Clover Field is the following statement;

"A pilot must have at least a private license.

"A pilot must have made at least five take-offs and landings within the past 60 days.

"A pilot must have logged at least 50 hours in aircraft of 90 hp or less.

"For any pilot who has never flown a Mooney, there must be a check ride in an aircraft of 90 hp or less prior to the first flight in the Mooney."

For a sportsman pilot who likes to hunt and fish alone in the most inaccessible of high-altitude spots, the Mooney would be ideal. It should prove a good salesman's ship since it will get in and out of relatively unimproved airports with ease, but the flying salesman must be able to put his order book and clean shirts in the 40-pound baggage compartment located directly behind the seat and accessible only by pulling the back of the seat forward.

The Mooney would be very practical for a large flying school for confidence-building cross-country trips since its operating costs are so reasonable. Factory tests have shown that the Mooney will fly 100 miles on from 73 cents to 84 cents worth of gas and oil.

If you really love the wild blue yonder and want to get away from the rat-race of constant contact with other people, the Mooney is an excellent vehicle. For small, high-altitude fields where the average ship puffs and groans, the Mooney is in its element. And for the Scottish pilot who frets about his gas and oil bills at the end of each month, the Mooney is hard to beat.

If you can fly alone and love it, be sure to try the new Mooney.

[This article first appeared in the August, 1949 issue of SKYWAYS magazine, published by Henry Publishing Company, New York. Our thanks to Denver Jacobson, C-GXTR, for providing it to us]

May 8, 2000