Mooney Mite

by Peter Bowers

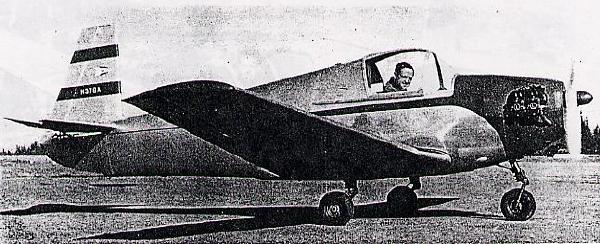

With five-foot, six-inch pilot at the controls, 1949 Mooney Mite equipped with 65-hp Lycoming engine gives impression of room vehicle. Photo by Peter M. Bowers

"Everymans" single seater fun plane, a revolutionary innovation for its day almost succeeded in beating the odds

The Mooney M-18 Mite was an interesting entry in the personal aircraft field in the post-World War II years. As an attempt to provide a minimum-cost and lively airplane for the sport flyer, the Mite challenged a number of hard facts of aviation history and economics. Thanks to clever engineering and sharp management, its manufacturer almost got away with it.

The Mite was introduced in 1948 by Mooney Aircraft Co., then located in Wichita, Kan. The firm was founded by C. G. Yankey and Al W. Mooney-former president and engineering vice president, respectively, of the Culver Aircraft Corp. after that producer of wooden personal aircraft had gone out of business early in the "iron bird" era.

Mooney had a number of well-known designs to his credit, including the Culver Cadet, some Monocoupes, the Dart, and the Eaglerock Bullet.

The now firm set up a small shop outside of Wichita. Overhead was low and labor costs were kept down by using part-time help already employed in other Wichita Aircraft plants.

Costs of the M-18 were kept to a minimum by using wood, with its reduced tooling costs, and a 25-hp Crosley automobile engine. The primary fault of the car engine for airplane use, notably its high crankshaft speed, was licked by using four Goodyear steel belts to turn the propeller at half the crankshaft speed.

The old problem of getting good air plane performance with minimum power was licked by using an efficient wing of relatively high aspect ratio coupled with a clean overall design.

The airplane itself was a little dream, a low-wing single-seater with enclosed cockpit, retractable tricycle landing gear, and flaps. The latter were interconnected with the stabilizer trim in the patented Mooney "Simpli-Fly" system that let one simple hand-crank operation take care of the simultaneous problems of flaps and trim for any desired flight condition. The whole tail unit pivoted for trimming.

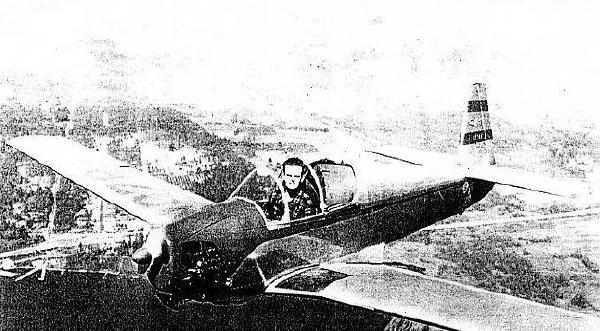

Peter M. Bowers, a six-foot-one, 195-pounder when this photo was made in 1950, found the Mooney M-18L a tight fit that almost necessitated flying with the canopy open for comfort.

To save further on weight and cost, there was no electrical system. This meant hand-propping to start, which, while still prevalent on the general aviation scene, was a bit of a chore because the prop was unusually low on the ground-hugging Mite. Many M-18 pilots who did their own starting stood behind the prop and flipped it, seaplane fashion.

Those who felt the need for radio installed a small battery-powered unit, on the floor in front of the seat. That was the only place where there was room for it.

The retractable landing gear used rubber biscuits for shock absorbers and was operated manually by shafts and push rods from a long lever in the cockpit. The travel of the handle was considerable and there was a trick involving acrobatics to getting the full travel and the necessary locking action at the end.

Watching a first-time Mite pilot take off was often hilarious. As soon as he got airborne, he'd start to pull the gear up. If he got into difficulties with the last part of the operation the lively little airplane would wobble around and start to wander off course. The pilot would let go of the gear handle and the wheels would drop back down while the airplane was getting the pilot's full attention and being put back on course.

The process would then be repeated. Often, the pilot would wait until he cleared the pattern and had plenty of altitude before getting the gear stowed. The same system, but with more elbow room is in some of four-place Mooneys being flown today.

In the absence of an electrical system to operate a "wheels-up" warning system, the Mite used a marvelously simple device-a pneumatic automobile windshield wiper tied into the intake manifold. If the gear was down and locked before the throttle was pulled all the way back, it pinched off the rubber vacuum line and the warning system remained inactive. If the gear was not down, a red flag above the instrument panel waved back and forth.

As good as the Mite was, it just wasn't good enough with the water-cooled Crosley. A change was made to the M18L model, powered with the 65-hp Lycoming O-145, after only five M-18s had been built. When .Lycoming stopped making the O-145 a few years later, Mooney adopted the 65-hp Continental A65 and designated the Mite the M-18C (not to be confused with the Crosley powered model, which was plain M-18).

The extra power made the Mite into a fine bird, with plenty of acceleration and a rapid control response that was a surprise to pilots who had trained only in contemporary 65-hp two-seaters. Since the Mite was a single-seater and a rental operator couldn't check new pilots out in it, the customary procedure was to take the renter up in a standard two seater to see if he could make good wheel landings.

In addition to the quick control response, one of the surprises that the little Mite handed to the low-time Cub pilot was its fast rate of sink with only 95 square feet of wing. Landings short of the runway were not uncommon among inexperienced Mite pilots.

For all of its merits and innovations, the Mite was still bucking history and economics. Man-hours, especially in wood, and material costs were not appreciably lower for a plane that was only slightly smaller than a two-seater that used the same engine and instruments. Further, the lower utility of a single seal limited it mainly to flying for fun and occasional personal transportation.

In spite of these problems, which had killed off other single-seaters in the thirties and had kept a couple of other promising postwar models from leaving the prototype stage, the Mite managed to hang on for eight years, reaching a production total of about 300. This was minuscule by contemporary Piper-Cessna standards, but was greater than the total of all other single-seat sport models built since the early thirties.

The labor market forced a move to Kerrville, Tex., in 1952, but the final blow came when Continental stopped building the A65. No substitute was available as there had been when the Lycoming went out of production.

Mooney was in production with the four-place Model 20 by this time, so the little Mite was discontinued. The fact there are still many on the FAA register is a tribute to the regard in which the little wooden wonders are held by their owners.

October 28, 2001