The weather over north central

Texas that warm spring afternoon was CAFB. . .a day just made for punching holes

in the sky.

The weather over north central

Texas that warm spring afternoon was CAFB. . .a day just made for punching holes

in the sky. The Infectious Mite

"It's just a real shame knowin' you're flyin' across the country with nothin' but a matchbox strapped to your ass." by M.B. Groves

The weather over north central

Texas that warm spring afternoon was CAFB. . .a day just made for punching holes

in the sky.

The weather over north central

Texas that warm spring afternoon was CAFB. . .a day just made for punching holes

in the sky.

I was enjoying the enjoyment of my toy, a "new" used Mooney Mite, and I'd been tooling around for about half-an-hour when I decided to head for home, via Amon Carter Airport. I figured I'd impress the Feds in the tower for a change.

There never was much doing over there, so they had plenty of time to be sticklers about radio procedures. And just before takeoff. I'd finished installing a new Narco 12-channel transceiver (complete with transmitter button on the stick), so I decided to give 'em a yell, just to let 'em know I was passing through.

Five miles ahead of me, a couple of huge concrete ribbons stretched across acres of spring wildflowers. Down there, on the rolling plains that kept Dallas and Ft. Worth at a respectable distance from each other, Amon Carter stood lonely. In those days -- in the Fifties -- looking down on the airport, it seemed as though some giant's kid had been playing "airport" out in the back yard . . .and then had gone off and left it.

There, plunked down in the middle of fields of bluebonnets and mustard weed, you could see a modern terminal, the American Airlines hangar, and a couple of smaller ones with an airplane or two scattered here and there. Across the way, there was the control tower rising up to the sky-overlooking plenty of nothing.

Making sure I'm in good voice, I clear my throat before punching the button on the joystick: "Amon Carter tower, this is Mooney Mite 4173, five miles southwest at 4000; heading eight-five. Any traffic?" (I know there isn't a thing but grasshoppers and bumblebees for miles.)

A voice comes right back, clear as a bell and with just a hint of Texas: "Mooney Mite 4173, say again your position."

What's going on? Am I garbled? Is something amiss in the tubes?

Self-consciously now, I speak a little louder: "Ahhh-Amon Carter, this is Mooney 4173, less than four miles southwest at 4000. Do you read?"

No reply.

I am now convinced that I've wired up something screwy: "Amon Carter, Do you read? Over!"

I hear the tower come on and, after a pause, a drawl comes through in lofty calm: "Mooney Mite 4173, you must be in error, relative your position. We don't have you on our radar."

What's this? They're saying I'm lost? Me? Lost? No way! Why, I'm midway between Dallas and Ft. Worth. There's Dallas, clearly visible to ' the east. And that's Ft. Worth. back there to my left. And there're the runways, the tower and Amon Carter terminal. Wot-the-hell, I can see it. Oh, wait a minute. . . either their radar isn't working... or they're pulling my leg. Don't have me on their radar, eh?

"Amon Carter, I have you in sight. Stand by."

I hear their confirming "click" as I take a few turns off the vernier throttle, slow up a bit, and then manually (how else?) lower the world's fastest retractable landing gear.

Click: "Ah hah! There you are, Moon-knee Mite Four-One-Seven-Thu-ree. We have you now. . .what'd you do, sonny, open up your little bitty canopy on your little bitty airplane, and wave yo' hat? No traffic. Have a nice flight, but y'all hurry on home now. Yo' Mama's callin'."

Tenderly working his vernier throttle, Dan Shumaker casually pulls

alongside for his portrait. Tenderly working his vernier throttle, Dan Shumaker casually pulls

alongside for his portrait. |

Very early production M-18 Mite displays super-clean

lines. Radiator for its liquid-cooled Crosley Cobra engine rides beneath the

fuselage. Very early production M-18 Mite displays super-clean

lines. Radiator for its liquid-cooled Crosley Cobra engine rides beneath the

fuselage. |

Is this the way it's going to be? One insult after another? "Little bitty" indeed! Here I am, flying one of the most efficient airplanes ever built, and I have to put up with sarcasm. Admittedly, Al Mooney's design is a bit small. But my Mite, grossing at only 850 lb., reflects years of work, optimizing on the design of a lightweight, low-wing, single-place airplane.

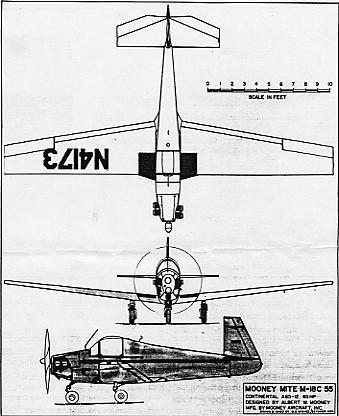

Fighter-like in appearance, it has an extremely clean airframe with a high aspect ratio wing. With the gear sucked up in the wing, it moves out smartly on its 65 hp Continental.

Al Mooney already had a string of successful, efficient designs to his credit by the time the Mite was conceived in 1946. Just 20 years before, at the age of 19, he was a draftsman and assistant to the chief engineer at Alexander Aircraft in Denver. It was from here that the classic OX-5 powered Eaglerock became a standard.

Later, as chief engineer at Alexander Aircraft (1928-29), he was responsible for the Bullet, an advanced, high-speed, low-wing monoplane. With Mooney-patented retracts, the Bullet was a mild sensation, and ahead of its time. On the other hand, it possessed some unusual spin characteristics. Although it was almost impossible to get one into a spin, once into it. . .

Then, at the height of the economic boom in the early part of 1929, he left Denver to form Mooney Aircraft Corp. in Wichita, Kan. Here, he designed and built a more advanced low-wing monoplane -- the Mooney A-1.

The A-1, like the Bullet, was designed for efficiency. And, in order to prove its performance early in 1930, Al decided to attempt a transcontinental, nonstop flight from Glendale, Calif., to New York. The A-l's normal, 46-gallon fuel capacity was increased to 186 gallons, and if the Kinner hadn't given up the ghost over Ft. Wayne, Ind.. some 22 hours later, he probably would have set a record.

Then the full force of the Depression hit the Mooney Corp. and, in 1931, it closed its doors.

By 1934, Mooney was with Bellanca, where he spent a short period as its chief engineer. It was during this period that he greatly influenced the design of the very successful Bellanca low-winged wooden wonders -- a version of which is still being produced.

|

Then, becoming vice president and chief engineer at Monocoupe Aircraft, another Mooney classic, the Dart, was produced. Unmistakably, the Dart had "Al Mooney" written all over it. And when Culver Aircraft purchased the design, prototype and tooling for the Dart, Al followed right along with it. During his days at Culver, he designed the famous and fully acrobatic Cadet.

With its elliptical wing and retracts, the two-seat Culver Cadet was efficiency unparalleled (and by then, the "Mite" was germinating). Over 350 Culver Cadets had been produced when World War II erupted.

The Culver Co. then turned to the production of radio controlled target drones and, by war's end, they had produced over 3,000 of the PQ-8 (a drone version of the Cadet) and PQ-14 (its successor) RC target drones.

The wartime, tricycle-geared, bright red PQ-14 was the direct ancestor to the diminutive Mite. In 1948, the Mooney Aircraft Corp. was resurrected in the hope of cashing in on the expected post-war aviation boom. its first offering had a span of 26 ft., 11", and sported a 25 hp, liquid-cooled Crosley Cobra automobile engine. The first Mite, with its now-famous "backward tail," hit the sport aviation world with a price tag of less than $2,000, and represented the cheapest, smallest aircraft to be produced in quantity.

During delivery of the first production Mite to a dealer in California the airplane was flown the 1,200 miles from Wichita to Santa Monica, with a total gasoline cost of $7.00. At 50 miles to the gallon and a range of 400 miles, a pilot's new dream ship was suddenly on the market. Full of innovations, it didn't have any weird flying characteristics -- well, except for a strange metabolic change that came over the pilot who "put" it on.

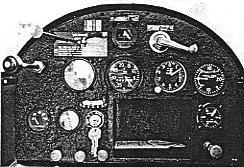

| The saddest day in a Mite owner's life comes the last time he screws himself out of the cockpit, and watches it fly away with someone else crammed inside. | With no radio, there's room for a brown bag, in-flight lunch in Dan Shumaker's M-18C. Upper left side of panel houses the Wig Wag (gear up) warning device included for the forgetful -- such as Al Mooney. |

|

|

|

|

| Rare shot of the M-19 "Cub-Killer" and close-in support weapon proposed to the Army during the Korean War. | The author's beloved Mite, as depicted in the drawing on the next page -- all yellow with black trim, complete electrical system, starter and generator. Gross weight (including author) 850 lb. |

| Dan Shumaker's spotless M-18C sits on the ramp at Tracy (Calif.) Airport. Flaps are lowered to the full down position. | After 15 "Mite-less" years, the author once again strains the load capacity of on of Al Mooney's designs. |

|

|

Once in the cockpit, the pilot, whose weight could easily equal 25% of the total gross, came close to satisfying any long-dreamed-of desires to be a fighter jock.

It drew attention everywhere it landed. People couldn't keep away from it or off it. And with that backward tail, it appeared to be super-fast. For speed, it achieved as much as one could expect out of whatever was up front, be it 25 hp Crosley, 65 hp Lycoming, or 65 hp Continental.

Economy and efficiency with the "big 65s" were incredible. Three and one-half to four gallons an hour, at between 120-130 mph, provided very cheap transportation and the greatest fun flying ever conceived.

There were a couple of drawbacks, however, that slightly impaired sales during its total production run of 264. One was the fact that a pilot was limited to what he could carry, since performance was highly dependent on pilot weight and how the aircraft was equipped. For example, my N4173 (one of the last produced) was the Cadillac of the Mites, it had the larger cockpit and canopy, and the Continental 65 had a full electrical system with starter and generator. After I'd swaged myself into the cockpit, I could (legally) carry a gallon and a half of gas!

The other drawback was the introduction of retractable landing gear to pilots who had been, in most cases, trained on Cubs. These low-time, Cub-trained pilots would get all fascinated with their landing approaches, and then make the most beautiful gear-up landings. Although always embarrassing to the pilot, the damage to the airplane usually was slight. However, the splinters from the 66" wooden Sensenich prop flying in all directions tended to attract attention.

It's reported that even Al Mooney did it while on a demo flight, and he had to make a very red-faced phone call back to the plant for a replacement propeller to be sent out A.S.A.P. After that incident, he invented the Wig Wag Warning device, which waves frantically when you throttle back with the gear up.

In May, 1951, during the Korean War, a frustrating attempt to militarize the Mite was initiated. On the strength of some frothy promises by the Army, the Mooney Co. conceived a counter-liaison, or "Cub-Killer," aircraft. At their own expense, Mooney outfitted a special version of the Mite, which company records show as: AIRPLANE, Liaison, Counter; Mooney Model M-19.

With this very military moniker, the Mite was then equipped with a constant-speed Flottorp prop in front of a 90 hp, fully cowled Continental power plant. Buried in the wing were two M1919A4, .30-cal. light machine guns. For an additional mission of close-in ground support, provisions for HVAR rockets under the wing made it a real potential killer."

The design gross weight was upped to 1450 lb. and, with the larger engine, it achieved a top speed of 150 mph. With Al Mooney, as well as military pilots, at the controls, the Army and Marine Corps were given impressive demonstrations of ground strafing and rocket runs. But no orders were forthcoming.

|

|

Shumaker's Mite carries a chocolate brown and white color scheme. |

This occurred during a time of strange and almost nonsensical inter-service rivalries. When the dust settled, the Army was not allowed to have any fixed-wing aircraft equipped with armament. It was established that this was to be (and still is) an Air Force responsibility. Therefore, Mooney had to abandon this expensive promotion, and the Mooney M-19 "Cub-Killer" became extinct.

Then, in 1953, in order to protect his work force from Wichita's proselytizing aircraft companies, Al packed up the "Mite works" and moved it -- lock, stock and welding equipment -- to Kerrville, Tex. Here, production on the M-18C-55 was continued.

This larger, canopied Mite soon evolved into the Mooney Mark 20 family. Configured with the Mooney trademark (the backward tail), the four-seat Mark 20 was a solid airplane that achieved 180 mph on a 180 hp engine. .

As soon as Mite production ceased, the airplane became a collector's item. Clubs sprang up, and today there is a Mooney Mite Owners Assn. from which complete drawings and assembly manuals can be ordered. The association (Box 3999, Charlottesville, Va. 22903) has sent out several hundred sets of plans to potential home-builders. But, so far, no home-built Mite has been completed.

Although basically just a fun plane to fly, the Mooney Mite can earn its keep. Whether used as an inexpensive vehicle for building up time toward a higher rating, or as a tow for gliders or banners, or even as a commuter airplane, its economic operating costs provide ideal transportation, especially for the individual long-distance traveler.

Although basically just a fun plane to fly, the Mooney Mite can earn its keep. Whether used

A California college student, Dan Shumaker of Livermore, has a Mooney N4142, and uses it regularly in order to visit his folks in Florida. Visits are great, but when it's time to return to California, Shumaker's canopy closes on his Dad's now-stock goodbye: "Son, it's just a real shame knowin' you're flyin' across the country with nothin' but a matchbox strapped to your ass." That's okay, Dan, it's all envy. Just envy.

This article is taken from the March, 1975 issue of the American Aircraft Modeler magazine.

August 8, 2001