A Mite Bit of Work: part III

by Dick Rank

(Reproduced

from the Minnesota Flyer magazine, March 1998)

Dick Rank built a Kitfox on these pages several years ago. Now he's back with a restoration project that he describes as "an ambitious undertaking but a very pleasurable learning experience. "

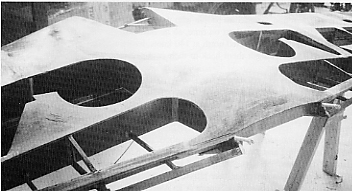

We have just come through many weeks of gluing one piece at a time into my Mooney Mite wooden wing after lengthy scraping, chiseling and cleaning where old parts were removed. When the glue goes bad in a wooden wing, every joint must be examined and repaired if necessary. Glues used in the 50s weren't meant to last 40-plus years. We are getting close to covering with fabric, and that is reassuring. But looking too far ahead asks for discouragement, so our focus remains on the interior of the wing.

|

| Most time was spent focusing on the Mooney's wing. |

Along the way I was given copies of the literature sent out by Fred Quarles after he bought the rights to this fine little aircraft from the Mooneys back in 1958. It was his plan to market it as a kit. Now being intimately familiar with the aircraft's interior, I would have to say that it would be a kit only for those who are over 21, who are very advanced aircraft woodworkers and who are under 30 so that they do not expire before finishing it. This Mooney design is very clever. Al Mooney was a genius. He used wood assembly techniques from the 20s and 30s that produce very strong and very light structures and added his own gift of design, but that type of assembly is very time-consuming unless done on a carefully worked-out assembly line.

|

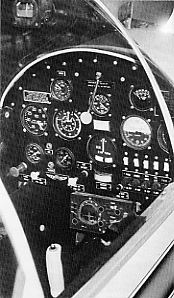

| Ben and Dick glue down the fabric on the wing. |

Inexperience also has something to do with the slowness of our progress. Cutting a plywood skin piece for the right wing took two hours. Cutting a similar one for the left wing took 10 minutes.

Mr. Ben, project boss and mentor, suggested that we take a day off and collect some useful aircraft information down in Griffin, Georgia, an hour's drive south of Atlanta. Translated, that means it's time for a rest and some goofing off looking at old aircraft. Two other good friends and helpers came along. Both are aviation buffs and excellent historians, since both were active in World War II. Since Ben also passed 70 a number of years ago, I was surrounded by members of the old-time aviation era when most airplanes had round engines, many had two wings, and goggles were necessary. Bits and pieces of aviation history were revealed all the way down to Griffin.

|

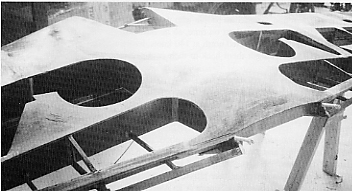

| The Mooney Mite is a platform for a sophisticated instrument panel. |

Within 10 minutes of Griffin there are three airports, and we hit them all. The first one, a small rural grass strip, has an FBO where old - really old - aircraft are rebuilt, like an Anorak C-2, an Aeronca C-3, a Kinner "Bird," a Tiger Moth and several more common models. Our interest was in another Mooney Mite, which was still a pile of pieces in the corner of a hangar. The wing was original and in reasonably good shape, however, so we were able to study it and photograph it as a guide.

|

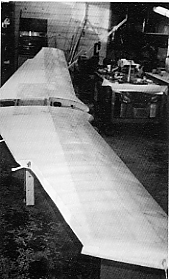

| The Mooney's wing is ready for paint. |

Airport No. 2, another rural grass strip, has the local Confederate Air Force "Dixie" wing hangar. Ben dropped off a treasure trove of old parts there, hoping that some will be useful to the CAP in the future. Inside the hangar were five devoted aircraft nuts lovingly restoring a very rare SBD Navy dive bomber from the Big One. Their intent is to restore it to its exact condition back in 1943, radios, guns, bombs and all. In order to do that, they often find themselves building components up from scratch, things like radio panels, skin panels, fuel tanks and controls. It is amazing how skill, patience and dedication can bring these historic aircraft to a state of new perfection. Looking at the aircraft now, the amount of work seems almost overwhelming. One step at a time will see it to completion, I'm sure. You will hear about or see this SBD at Oshkosh and in the magazines, without a doubt. Examining the SBD was very special, since one of our traveling companions flew them in World War II. After viewing the cockpit, now perfectly restored, he confirmed that everything was in the right place. He also observed that he could get in it right now and fly it well. No one doubted that. What is it they say about riding a bicycle? After that very interesting visit we went on to the Griffin Municipal Airport, the largest of the three, where there are several rebuild facilities operating. Outside I counted three DC-3s awaiting work, two old DC-4s set up for oversized cargo, a Navy Panther jet and two square blocks best described as an aircraft junkyard. Everything there is very expensive junk, however.

Inside our hangar of destination was a very familiar tail assembly, a long, narrow horizontal stabilizer with oval rudders on each end. It appeared new from tip to tip, and it was faultlessly assembled, including some really complex components. The front of each end attached to separate fuselage booms, confirming that it was a P-38 tail. Questioning revealed that it was for the P-38 recovered from under the Green- land ice by Pat Epps and his group of adventurers two years ago. Apparently, the pressure on the tail assembly 250 feet under the ice cap had bent and crushed the relatively delicate tail beyond repair. The rebuild job was given to Jon Neal because of his craftsmanship. The old, crushed components were hanging on the hangar wall, painted in 1943 olive drab paint with yellow numbers. It is so fascinating to be able to actually touch that part of our aviation history.

A late lunch at an old country barbecue restaurant finished the day properly, and we were all ready to go back to piecing together my Mooney Mite in Atlanta. How's that for a good aviation day? Now if I could only get Ben to drive a little slower!

***

The clock is ticking. Sun and Fun starts April 6, and here it is, mid-January, and I'm still working on the wing. The fabric is on, finishing tapes are glued down and ironed, and we are finally ready to spray on the filler coats. The landing gear has been bead-blasted and painted white, and it looks new and ready to retract into the white wheel wells. We might not be ready by April, but that's OK. Things have to be done just right even when you can't see the craftsmanship.

While pulling off the fabric on the tail feathers, we found a cracked stabilizer spar, and one phone call located another, which we ordered out immediately. After covering that one-piece wing, covering the tail will be a piece of cake. An AD called for installation of a number of inspection holes in the rudder, elevator and stabilizer, and all were properly complied with.

Covering is surprisingly fun to do. It's one time when you can really see the results of your efforts. Tightening the fabric and painting the first coat really brings things together, making assorted pieces look like an airplane again. Doing the decorative detail is another matter. It took several tries to get a nice, clean, sharp edge to the lines where white meets red. Using high-quality masking tape is very important. Regular masking tape may take off a layer of paint as you pull it off. Not good.

Rigging the airplane to fly straight and true went without a hitch. However, we had discovered and removed five pounds of lead from the right wing tip at disassembly, and so we weren't sure how level it would fly during the test flight. More about that later.

Many happy circumstances arose as work progressed. One day a gentleman walked in and asked if he could help. Happily, he was a retired aeronautical engineer from Lockheed, having done work on the C-130 and other Lockheed projects during the last 30 or so years. Bill Wegman was every builder's dream. He had the answers when I asked about the effects of adding gap seals where the underside of the flaps meets the wing. We decided not to do it because it would reduce flap effectiveness, even though there would be a slight speed increase. When it appeared that the nose- wheel mount needed to be trimmed, he came in the next day with actual figures on how much strength we would lose by trimming the yoke one-fourth or one-eighth of an inch. We had excellent help from several "gray eagles" throughout the project.

|

| Bill Wegman, retired Lockheed engineer, test spins the prop, carefully supervised by Ben Epps and Jim Clarkson, an AI. |

Weight and balance needed to be re-established, and the hangar boss at the Epps FBO said he needed an airplane in order to demonstrate a new set of electronic scales and teach their use. Naturally, I was able to help the poor man out. I graciously made the Mite available to him immediately. On another day the records and technical compliance guy handed me a nicely bound copy of all ADs on the air- craft, the engine and the propeller so we could take care of those items. I felt very fortunate indeed. The community spirit and helpfulness of people in aviation never cease to amaze me.

As we drew close to the test flight, I relished every task because I could see the end in sight. Tests were run on the engine, and it appeared to be ready. We called in the inspector to have a look and sign off the Mite. By now, a lot of people had a stake in the safety and good performance of the Mite.

|

| Towing the Mite out for its first flight. |

The day finally came when I climbed in and started the engine for the test flight. I had planned every move. The first flight was to be on the long runway (6,000 feet). I had already done a series of taxi tests of brakes, engine and controls. This was the time when all the hard work should pay off, and it did. The airplane climbed out nicely at about 600 fpm with the gear remaining down. I didn't want to deal with that on the first flight. Once around the pattern and down again showed just how easy it is to land a Mite. Just get set up at 65 mph on final, dropping 400 fpm, flaps and gear down, and wait till the last second to flair. It just lowered itself to a perfect squeaker. That was enough for one day. I taxied back to the hangar and we all celebrated a winner. But the work still wasn't over. Sun and Fun had come and gone and we weren't ready for Oshkosh just yet.

Last page (Bringing the Mooney Mite home)

Our thanks to Dick Coffey and the Minnesota Flyer magazine, in which this article first appeared.

October 20, 2000