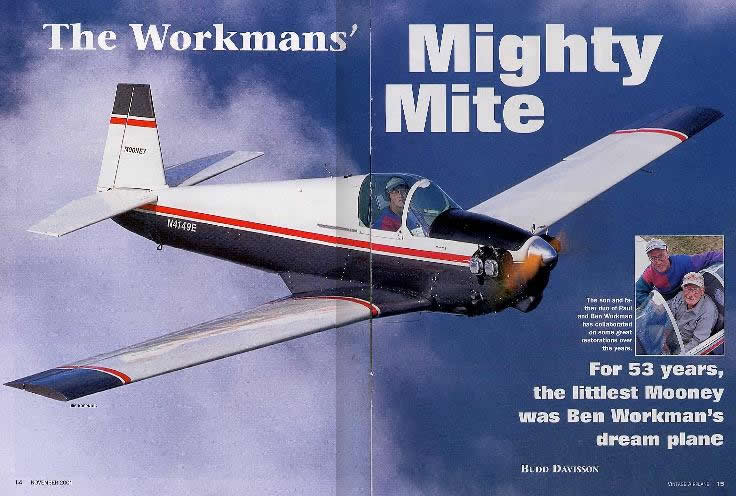

The Workmans' Mighty Mite

by Budd Davisson

This article is taken from the November, 2001 edition of the EAA's Vintage Airplane magazine.

Ben Workman was standing in front of his Mooney Mite and summarized one of its few drawbacks by saying, "It's not an airplane for guys with either big feet or big bellies."

Ben says his urge to add a Mite to the long, long list of aircraft he has owned and restored started back in 1948 when he got a single flight in one. When he landed he said to himself, "I'm going to own one of those some day." The airplane seems to have the same effect on lots of people.

The Mooney M-18 Mite is one of those airplanes that newcomers to sport aviation find hard to believe is a fully certified, factory produced airplane. It seems almost inconceivable that there was a time when an American businessman had enough guts to put that much time and effort into an airplane that is not only the aeronautical definition of "cute," but would stretch the limits of the definition of "utilitarian." Of course, in 1948 someone did just that and that someone was the always-visionary, always-thinking Al Mooney. For nearly three decades his mark was made on aircraft from Monocoupes, Darts, and Cadets to the famous line of Mooney aircraft. In fact, it would be easier to name aircraft he didn't have a hand in than those he did.

|

The Mooney design philosophy always put efficiency right at the top of design parameters, which eventually led to lots of high aspect ratio wings coupled to compact cabins being dragged around by smaller than normal engines. Of course, the M-18 Mite (which some sources say was originally called the Wee Scotsman) carried all of these factors to their logical extreme.

Mooney's goal all those years ago seems to still be with us today: He wanted to design the fastest, most economical airplane possible. This required the smallest, lightest, and cleanest airframe he could design mated to the least expensive, most fuel-efficient engine available. In both areas, he went to extremes. The airframe is a study in light wood construction. It has been often said, for instance, that anyone who picked up one of the tail surfaces— and saw how light and fragile it appeared—would never fly the airplane. The tail is unique for a lot of reasons, including the fact that it isn't mounted to the airframe in the usual fashion. The entire unit pivots for trim and is mounted on a light steel tube tripod that is, in turn, bolted to the rear fuselage bulkhead with tiny-appearing No. 3 bolts. The entire tail, including the wood, the steel, and the bulkhead area are now areas of concern to restorers because of the way seemingly minor deterioration can reduce the strength significantly.

Another of Mooney's cost-cutting, efficiency-seeking moves was to sidestep expensive aircraft engines. Instead, he mounted one of the miniscule, 22 hp Crosley engines, which are best known for propelling the little Crosley station wagons. The engine was highly sophisticated in that it was a single overhead cam design, which was manufactured from sheet steel and brazed together in an oven. You can literally tuck one of these engines under your arm and walk off with it. In the Mite it was equipped with a 2:1 V-belt reduction unit. The first 10 airplanes were Crosley powered, but then the gremlins that always seem to afflict an otherwise healthy engine, once it's mounted in an air- plane, reared their ugly heads and crankshafts began breaking (Crosley reportedly switched to a cast iron crank from a steel crank without letting Mooney know). A switch was made to the 65 hp Lycoming 0-145, then later to the A-65 Continental.

|

About the time Al Mooney was gearing up to feed airplanes into the highly anticipated, but never realized, post-war airplane market, Ben Workman was getting out of the US-AAF. He had worked at Curtiss Wright's Columbus, Ohio, factory (working on Helldivers and their ill-fated Seagull) before entering the Air Corps. He even had his own 40 hp J-2 Cub during his early years in the service. He flew 28 missions as a radio operator on board B-24's with the 34th Bomb Group before going home to decide what he'd do with the rest of his life.

As with many returning servicemen, the GI Bill gave Ben his ratings. He had been to mechanics' school before entering the service, so armed with his A & E ticket, he began working for a local FBO while getting his flight ratings. Then he drifted into auto repair, which led to an upholstery shop, which, in turn, led to him owning his own auto and aircraft upholstery business. The business is still alive and well in Zanesville, Ohio, where it is being run by his son, Paul, who brought the Mite to AirVenture 2001.

|

Ben ran through a long list of aircraft projects that eventually involved his two sons, Dave and Paul. He bought a basket case Cub and he and his older son, Dave, restored it. They took it to Oshkosh in 1972 where it won Best Under 100 hp. During the next 10 years, Ben and Dave built and flew what they dubbed the Pitts Sport, which was a hybrid biplane with a 90 hp Franklin engine. During this time Dave restored another Cub and most of a Tiger Moth before he passed away in 1982.

In the late 1970s Paul became more involved in the family business and developed the same love of aviation. After Dave passed away, Paul and his dad went to work on a 7FC Tri-Champ, which had been wrecked. Besides restoring it, they converted it to a tailwheel configuration. By 1986 Paul was married with a growing family so the decision was made that he and his dad had to begin working on a four-place airplane. Enter the Aeronca Sedans.

The first Sedan came from Canada. They restored it and flew it for nearly 16 years before selling it. A year and a half after finishing the first one, they bought another Sedan and spent two years restoring it. In '92 it was Grand Champion at Middletown. It went to the EAA's Buck Hilbert who won a Lindy with it. The airplane currently is owned and flown by EAA director Verne Jobst. Vintage Airplane's editor, H.G. Frautschy, takes care of the Sedan and also flies it on a regular basis. When first restored, it was probably the lowest-time Sedan in existence, with fewer than 250 hours on it, total time!

|

The Mite entered the Workmans' lives about three years ago.

"It was advertised as being in good shape, but the further we got into it, the worse it looked," said Ben Workman.

"It had set outside and moisture had really gotten to it. Both the front and rear bulkheads were being held to the tail cone by nothing more than fabric," he says. "Everywhere you looked in the lower parts of the fuselage and wing center section, the casein glue was coming apart. This included the plywood facing on the spars."

They began tearing the airplane apart and eventually had virtually every nut and bolt out of it in their search for moisture damage to both the steel tubing and the wood. This included re-gluing most of the joints in the fuselage and replacing much of the wood.

"The landing gear needed lots of work and one gear leg was bent," Ben says. "I didn't know it was hardened and I stuck it in a vice to try and straighten it. It was so hard that I broke it and had to call Fred Schmidt in Camden, Ohio, for another one. He has by far the best supply of Mite parts. That's also where I got parts for the windshield wiper motor that is used as the gear- warning indicator."

The gear-warning indicator he is referring to is the small flag, not unlike that on a mailbox. It begins waving if the throttle is reduced below a certain level and the gear isn't out. The wiper motor is driven by vacuum tapped from the intake of No. I cylinder.

"The tires were really hard to find,"

Workman says. "They are four hundred by fours and were never FAA certified. They

were certified as 'Mooney' parts. The brakes are purely mechanical and use an

eccentric to move the pads out. The gear is also sensitive to rigging and the

down lock is the same mechanism that locks the gear handle in the down position.

It's easy to do wrong and this airplane has been on its belly at least

once."

"The tires were really hard to find,"

Workman says. "They are four hundred by fours and were never FAA certified. They

were certified as 'Mooney' parts. The brakes are purely mechanical and use an

eccentric to move the pads out. The gear is also sensitive to rigging and the

down lock is the same mechanism that locks the gear handle in the down position.

It's easy to do wrong and this airplane has been on its belly at least

once."

The airframe did have some good news attached to it, despite all of its problems. "The outer wing panels, the fuselage tubing, and most of the tail were actually in pretty good shape. Everything in between, however, needed lots of work."

|

The finish and covering was Super Flite II all the way and Ben Workman points out that the light gray color isn't paint, but is actually primer that has been clear coated. They saw the color of the primer and both liked it. So, rather than try to match it in paint, they just hit it with the clear coat to protect it.

The finished airplane came in at 625 lbs and it really performs, according to Paul. "It gets off fairly quickly. The engine is only turning up 2,050 rpm with that prop, but it still only needs about 400 feet of runway. I hold about 70 mph in the climb which gives a solid 600 to 700 feet per minute rate of climb."

In cruise the airplane will true out at 120 mph at 2,250 rpm. The beauty of it, however, is that it is burning only four to four-and-a-half gallons per hour.

"The airplanes with the Beech-Roby props are faster, some as high as 135 mph. The never-exceed speed is only 139 mph, so that's crowding it pretty close," Paul says.

"The gear down speed is 108 mph," Paul continues, "So, you can slow it down quickly and it needs the drag to get it to come down. There is no trim change when the flaps go down, because they are coupled to the tail. I use 65 to 70 mph on final and it gets in and out of 1,800 feet of grass nicely. It does glide well, so you have to plan the approaches a little better than with some airplanes."

So, now Ben Workman has that airplane that he once told himself he'd own someday. The beauty is that it only took him 53 years to do it!

Aerial photos by Jim Koepnick. Ground photos by Mark Godfrey.

Reprinted with permission, ©Vintage Airplane 2001.

November 29, 2001