Magic Carpet Ride

The Mooney Mite Turns 50

Text and photos by Vicki Cruse

I CAN STILL REMEMBER the first time I ever saw one. It was on the ramp in Winter Haven, Florida. The faded, yellow fabric and paint dulled from the sun, and the dirty canopy told me this airplane had seen better days. I immediately noticed the distinctive Mooney tail, but thinking it might be some obscure homebuilt, I asked, "What is that?" I was told it was a Mooney Mite, and my response was, "You've got to be kidding me! Mooney made this?" Despite the shape of the tail, I could hardly believe this airplane was made by the same people who put out the 201 or the Ovation.

If you are under 40, you may have never heard of this airplane, much less actually seen one. Most people, upon seeing one for the first time, give a little chuckle and think the person is joking when they say it's a Mooney, but the Mite is the airplane that launched Mooney Aircraft in 1948. It went into production in 1949. This year is the 50th anniversary of the Mite, as well as of Mooney Aircraft, although Mooney sold the rights to the Mite long ago and has essentially disowned the aircraft altogether.

When I mentioned doing a story on the Mooney Mite to a friend of mine in his mid-50s, his first reaction was a raised brow and a sarcastic, "Why?" He thought no one would really be interested in the airplane, but I explained that people my age or younger probably didn't know much about the airplane at all. As we talked more about the airplane, he confessed that he had once thought of buying one. In college, he used to drive several hundred miles on week ends to see his girlfriend - a trip that would take a few hours in a Cub or Taylorcraft. When the Mooney Mite came along, visions of making the trip in little more than an hour made a real impact on him.

The Mite was economical and fast; my friend called it the "magic carpet ride" of its time. It was exactly this notion, minus the magic carpet ride, that Mooney used in its advertising campaigns. In a 1955 brochure, it was called "the most personal, most timely airplane ever built!" and was said to fly at an average cost of 1.3 cents per mile, compared to 3.6 cents per mile for the average car. The airplane was not only economical, it was fast, cruising at 125 mph with 65 hp. Mooney targeted businessmen, and the sales brochures were filled with "business features" and slogans such as, "On the ground and in the air, the Mooney Mite sets new standards for the flying businessman." Within five years, Mooney saw the need for a multipassenger airplane that provided both speed and comfort. This, and a lack of engines, put an end to the "businessman's airplane."

The M-18 Is Born

In the late 1930s, Albert W. Mooney became the chief engineer of Culver Aircraft Corporation and designed the first Culver Dart, which grew into target airplanes for the Air Force and Navy. Shortly after these aircraft were put into production, the Culver company was purchased by Walter Beech, who moved the production to Wichita, Kansas, near the Beech factory. Al Mooney remained the chief engineer at Culver.

Shortly thereafter, the Culver V was announced and put into production. This design incorporated a number of innovations Al Mooney had long felt were needed for an airplane. However, the airplane did not prove to be a commercial success, and Culver Aircraft was dissolved.

In the late '40s, airplane manufacturing started going from wood to metal, and personal aircraft such as the Navion, Cessna 195 and the then Temco Swift were rising in price. The Navion was approaching $10,000, the 195 listed at $13,750 and the Swift was up to $4,495. Just as today, each price increase moved the airplanes out of the hands of those who wished to have one. Along came Al Mooney, who, in 1947, built himself a little airplane that attracted so much attention, he formed a company to produce it. Mooney Aircraft was born and so was the Mooney Mite, with an amazing sticker price of $1,600.

The Most Business-Like Airplane Ever Built

The prototype Mooney Mite, designated the M-18, was flown in late 1948. It was a single-seat, low-wing monoplane constructed of a fabric covered, welded steel-tube fuselage. The wings were wood, plywood and fabric-covered, with plywood leading edges. The tricycle landing gear was fully retractable. The cockpit utilized a sliding canopy and standard instruments, including an airspeed indicator, compass, altimeter, tachometer, oil pressure gauge, ammeter, oil temperature gauge and fuel gauge. This construction and standard equipment would stay the same through the airplane's production life, with a few options available in its later years.

The aircraft is small, weighing in at only 500 pounds. The highest point at the top of the tail is 6 feet, 2-1/2 inches, and the wingspan is 26 feet, 10-1/2 inches, with 95 square feet of wing area. The aircraft holds 12 gallons of fuel directly behind the pilot's head and uses a gravity-fed system with a clear sight tube to determine the fuel level. The baggage area can hold 75 pounds and is accessed by hinging the back of the seat forward from its base. Gross weight was originally 780 pounds but was later bumped up to 850 pounds with a change in engines.

The prototype was priced very low, and Mooney had every intention of keeping it this way. However, a poor engine choice from the beginning changed the bottom line in a hurry. The original aircraft utilized a 25-hp, water-cooled Crosley Cobra engine - the same engine used in the Crosley automobile. The engine was geared down and turned a wood Sensenich fixed-pitch prop. Problems with the engine quickly surfaced, and after only five M-18s had been built, a change was made. The M-18L model was created, and it was powered by a 65-hp Lycoming O-145. Production began in 1949; 66 airplanes were produced that year. Eighty-one M-18Ls were produced before the factory raised the gross weight on the airplane from 780 to 850 pounds, while also giving buyers a choice of engines: the 65-hp Lycoming, designated the M-18LA, or the 65-hp Continental, now called the M-18C. List price for a 1951 M-18LA was $2,516.67.

In 1952, Mooney moved its operation to Kerrville, Texas. The final Mite model, designated the M-18C-55, was produced in 1955. It was only available with a Continental and was equipped with a larger canopy and cockpit. It listed for $3,695. The Mite's downfall occurred when Continental stopped building the A-65 and Mooney stepped up production of the four-place Model 20. A total of 283 Mites was produced between 1949 and 1955. Of these, 126 were powered by Lycoming engines, and 157 were produced with Continentals, of which 35 were C-55s.

Mooney Aircraft sold the rights to the Mooney Mite several years later, and all attempts that were made to produce the airplane as a kit failed.

"Mitey" Features and Performance

The Mooney Mite had some unique features for its time. The airplane had flaps, retractable gear and the patented Mooney "Simpli-Fly" system that let a one-hand crank operation take care of simultaneous problems of flaps and trim for any desired flight condition. When you crank the trimtab, the rudder, elevator and tail cone, all move. Keep cranking, and the flaps come down but only after the stabilizer is rolled all the way back. The system is unique, and Mite owners say the system worked flawlessly.

The Mite had no electrical system, but this option, along with a starter, was available later in production. Hand-propping the airplane could be a chore, particularly for taller pilots, since the airplane was so low to the ground. A popular technique for starting was standing behind the prop and flipping it, seaplane style. Radios were not available in early models, although a number of pilots used a handheld placed on the floor in front of the seat - the only space available for one.

The nosewheel is steerable and retracts into a compartment in the fuselage floor. A small window is located near the floor in the center console to verify that the wheel is straight before retraction. Steering was accomplished by differential braking, and steering was not as easy as it looked. Pilots used to the hairpin turns of the later Mooneys were very disappointed with the Mite - a tight turning radius was not one of its attributes.

The retractable gear was operated manually by pushrods and shafts from a long lever mounted on the right side of the cockpit, just aft of the pilot's ankle. The travel on the handle was considerable and required some in-flight acrobatics to reach it and get full travel out of it. In a 1949 article for Skyways magazine, Don Downie wrote, "Getting the gear up is an interesting experiment. It takes quite a little pressure to unlock the gear. However, once it is disengaged, the handle swings back easily until it is 3 or 4 inches short of the up-and-locked position. The pilot must apply considerable pressure to force the gear handle into the fully retracted lock. A lightweight gal pilot might find considerable difficulty in locking this gear, but if the pilot has normal strength in his arms, the whole arrangement is very neat."

|

The Mooney Mite also had an interesting device for letting you know the gear was down: a red dot about the size of a 50-cent piece on the end of a 6 inch rod mounted at the top of the instrument panel. If the gear is not down and locked as the throttle is brought back beyond 1200 rpm, the rod wags back and forth like a wind shield wiper. The device is driven from the intake manifold. Without an electrical system, there is no gear-down light or horn, but there was no mistaking this device waving in your face.

For its day, the Mooney Mite was a unique airplane. Powered by only a 65-hp engine, the Mite cruised at 125 mph. At gross weight, the airplane required 300 feet for takeoff and 275 feet for landing. The stall speed with the gear and flaps down was 43 mph. Rate of climb was 1100 fpm, and the time to climb to 10,000 feet was 12 minutes. The fuel burn of the airplane was provided in a rather unique way: 35 to 40 miles per gallon, with a range of 450 miles. This works out to a fuel burn of about 3.5 gph.

Fuel capacity in the prototype was 8 gallons but later increased to 12 gallons. A later option added a small, 6-gallon tank in the wing. The M-18C-55 had a standard 16-gallon capacity. Mooney's 1951 Mite brochure provides a yearly operating cost of $674, based on 300 flying hours. Fuel at that time was 30 cents per gallon and oil was 40 cents per quart. Maintenance was calculated to be $25 per 100 hours, and insurance was $260 per year.

|

According to Mooney, "For each flying hour, this cost figures out to be $2.25 per hour; at 120 miles per hour, the figure is $1.88 per 100 miles, or less than 2 cents per mile." A typical business trip from Chicago to Cincinnati of 270 miles would take about two hours and 15 minutes at 120 mph, with the total cost of the trip calculated to be a minimal $5.08. You can see why Mooney marketed the airplane to business men; they not only had the money to buy the airplanes, they also had a perceived need for the airplane to make their trips more economical.

A Sweet Airplane

It's difficult to research the number of Mooney Mites still flying. Although there are over 100 still registered with the FAA, determining the number still in flying condition is nearly impossible. Through sheer luck, thanks to the Copperstate Fly-in, I got acquainted with Garry Gramman of El Cajon, California. Gramman is the original owner of N119C, an M-18L built in September 1949. The airplane has almost 1400 hours on it, and Gramman still flies it.

|

Gramman first flew a Mooney Mite in late 1949 and initially, didn't have an interest in buying one. He had 40 hours divided between an Aeronca trainer and a J-3 Cub, but the Mooney distributor in El Cajon convinced Gramman that he needed a Mooney Mite and that he could make money on it. Seeing a possible money-making opportunity, Gramman took the bait and bought Mite N340A in May 1950. The distributor took care of the maintenance and rented it out, with a portion of the rental fees going to Gramman. A few years of little return on his investment and a move took Gramman and the Mite away from Gillespie Field in El Cajon, only to return a few years later, but without his association with the distributor.

You might be wondering why Gramman's Mite started its life as N340A and is now N119C, which is in sequence with model year 1950 Mooney Mites. (Mooney chose sequential N-numbers for the Mites, although they do not correspond with the serial numbers.) In 1950, with only 70 hours on the airplane, Gramman flew to Phoenix, Arizona, and was caught in wake turbulence from a DC-6. He crashed the airplane but limped away. The wing was damaged, and the fuselage was crushed.

He decided to have the airplane rebuilt and took it back to Gillespie Field, where it was boxed and shipped to the factory in Wichita and put back on the assembly line. When it came time for the wings, the next set in line was numbered N119C. Mooney Mites originally had the N-number painted on the top of the right wing and side of the fuselage. While some Mites retain those original markings, Gramman's does not. So, N340A became N119C, and Gramman had his airplane back.

In the years since acquiring the airplane, Gramman has made a few changes.

|

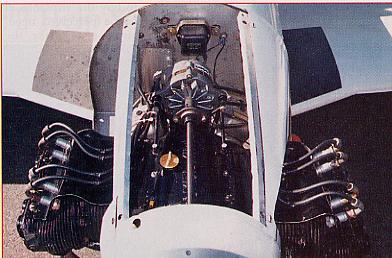

His airplane has an electrical system that he installed, as well as an automobile alternator mounted atop the rear of the engine. The gear-down flag is gone, replaced by gear lights and a very loud horn. I was a little disappointed to see the flag missing; previous articles on Mites from the 1950s touted its uniqueness, and I wanted to see the flag in action. The panel was redesigned and is IFR-equipped; thus, the need for the 35-amp alternator Gramman also modified the engine to produce 75 hp, instead of the usual 65 hp. The original prop was a Sensenich, but Gramman replaced it with a Flottorp, which was an option on later Mite models.

Since the airplane has been out of production for almost 45 years, I asked Gramman how he deals with maintenance issues. He said there are still parts available, but those that are not must be custom-made. Mite owners often have spare engines (Gramman has two), although he says the engine parts don't tend to wear out. Regarding parts, he said, "Sometimes, you have to scramble and use your ingenuity, but it can be done. If you have a part you aren't using, you never throw it away because sometime, either you'll need it or another person will."

Besides having an airplane that will turn 50 this year, Gramman is an interesting and persistent guy. A week after I visited him, he turned 77, but you wouldn't know it by his enthusiasm for his Mite. While Gramman has owned his Mite for almost 50 years, he's only flown it for 25.

|

He lost his medical in 1968 and didn't get it back for 25 years. During that time, the Mite sat outside, alone, and Gramman decided to use the time to give it a little TLC and rebuild it. It took him about 12 years, right up to the time he got his medical back. The day after his medical was reinstated, he flew to a Mooney Mite gathering in Porterville, California, and said it was one of the most memorable flights he's ever taken.

When asked what he likes best about the Mite, he said it's the trim system. In a cross-country configuration, the airplane flies hands-off, and to begin a turn, Gramman can just lean in the direction he wants to go. As for what he likes least, he said it's the fuel capacity of 12 gallons. While it can go for about three hours and just over 300 miles, he said there are times he wishes he had a little more capacity. The longest trip he made was in 1952, to see his family in Indiana. He traveled the 1700 miles in one and a half days. He still remembers the 15 minute fuel/bathroom/sandwich stops, flying over the Republican National Convention in Missouri, where Dwight D. Eisenhower was nominated, and racing home to the girlfriend who later became his wife.

|

One of the obvious disadvantages of the Mite is its inability to carry passengers, and this led Mooney to design a multi-passenger airplane. When asked if he ever wished the airplane had more than one seat, Gramman said he's only wished for that a few times. When he lost his medical, his company had just purchased a Mooney Executive 21F, so carrying passengers was no longer a problem. He said he has thought from time to time that he might like to have a four-place Mooney, but when he asks himself why, he never has a good answer, since his wife really doesn't like to fly.

Obviously, Gramman loves his Mite or he wouldn't have rebuilt it twice and kept it for almost 50 years. Describing his airplane, he said, "She's such a sweet airplane."

Mooney Mite Owners

Mite owners are a unique bunch. Despite the age and scarcity of the airplane, Mite owners and

|

enthusiasts have an association called the Western Association of Mooney Mites (WAMM). It is based in California but includes Mite owners across the United States. The group holds at least two fly-ins each year on the West Coast, and members in the eastern United States also try to hold a fly-in each year. The Western fly-ins for 1999 will be held in Porterville, California, from May 14 to 16, and in Redding, California, August 27 to 29.

The East Coast fly-in has not been announced yet, but for more information or to join WAMM, contact Anthony Terrigno, 18020 South Trail, Chino Hills, California 91709; 909/597-7449.

What started out as a personal "rocket ship" for Al Mooney, the beginning of Mooney Aircraft and a magic carpet ride for hundreds of pilots has become a rarity that brings inquisitive looks wherever it goes. Marketed as the businessman's air plane 50 years ago, the Mooney Mite remains a mystery to the majority of pilots who have rarely had the chance to see one up close. With people like Garry Gramman still flying, many more people may yet get the chance to see this "sweet airplane."

This article was first published in the April 1999 issue of Custom Planes magazine.

August 16, 2001