A Mite Bit of Work: part II

by Dick Rank

(Reproduced

from the Minnesota Flyer magazine, February 1998)

Dick Rank built a Kitfox on these pages several years ago. Now he's back with a restoration project that he describes as "an ambitious undertaking but a very pleasurable learning experience."

Ever since I bought that forlorn-looking Mooney Mite several months ago, nice things have been happening. There is no better group of people than those in the aviation community. So many have offered help in the rebuild process.

|

| Ben and helper, ex-SBD pilot Johnny Caldwell, view the wood rot in the center wing. |

Part of the fun of this project is searching for the history of 118C. In searching back through the record of owners (the Mite was assembled in 1950), I was able to locate the fourth owner in Caldwell, Montana. I called him, and he spent the better part of an hour on the phone with me, telling me interesting facts about N118C's history.

Larry Johnson, the previous owner, was a P-40 and P-47 pilot in World War II, and he was shot down over Italy and spent time in a German prison camp. The Mite was a great favorite with him because, although tiny in comparison to his Jug, it flew and felt like a fighter with its bubble canopy, low wings and cramped cockpit. He spent many happy hours in it.

A week after our conversation, I received a package from him, and in it were many copies of the Mooney Mite Owners' Club newsletter from the 1970s, pictures of many Mites and several color pictures of my aircraft taken back in the 70s. There was even an advertisement for a Mooney Mite kit, offered by someone who bought the manufacturing rights after Mooney stopped making Mites.

George Jevenager, a regular out at Flying Cloud Field and a Mooney Mite owner, was kind enough to show me his aircraft, and he provided a copy of the "Mooney Mite Wood Repair Manual" so that Ben and I would know exactly how to properly cure the Mite of its wing problems. And while spectating up at Anoka Aviation, who should I see but Duane Flackbarth, proud possessor, with Durber Allen, of a 1995 Oshkosh blue ribbon for the outstanding restoration of his Mite. Needless to say, I was provided with a mass of information from him about how to go about the restoration process, and his Mite was right there to study.

|

| Anoka's Vern Flackbarth was there to offer help. |

While trading ideas, another friend came up and, in the course of conversation, mentioned that he had tucked away two Lycoming 0-145 engines that fit my Mite. We will have further exchanges about that, I'm sure. My guardian angel continues to look after me.

The one-piece wing will get immediate attention. Being outside for two years is not an appropriate situation for any wooden aircraft, and the Mite's wing showed the results. The center section surrounding the fuselage was most deteriorated, and much of the deterioration was not visible from the outside. Over 100 small gusset pieces needed replacement where ribs meet spars. The rear spar was rotten and delaminating. Flap and aileron attach points were loose. Much of the 1950 glue had turned brittle and crumbly - scary to think about if the aircraft had been ferried. The wing interior had never been varnished, so normal condensation had rusted nails and softened wood in places. Seeing the inside of the wing was an eye-opener. If you have wooden wings, examine them regularly and fly the airplane regularly to dry out the moisture.

|

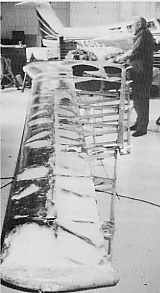

| A little "body and fender" work was done to smooth uneven plywood skin. |

Manufacturing the seven-foot rear spar was an interesting and lengthy task. Ben Epps, my mentor, had several old and beautiful Sitka spruce spar blanks in his wood loft, so laminating strips were cut from one and a steel gluing jig was built from salvage steel. Glued up in four phases, the finished spar is pretty enough to be framed. Faced with aircraft-grade mahogany plywood, it is a perfect replica of the original, but much stronger. I can relax knowing it is under me. Building it took so many hours that making final cuts for length and drilling holes was a tense process. However, we got through it without any errors.

The 1/8-inch plywood webs on front and back of the main spar had come loose from the wood underneath, and there was some rotting at the bottom of the spar. Fortunately, the repair manual allows partial web replacement so long as joints are either wide-beveled or if doubles are glued over the original plywood at the joints. Every one of these discoveries meant learning a new woodworking technique. No complaints. That's what I wanted.

|

| Dick Rank checks the wing glue joints. |

With Ben's help, I was able to replace two odd-shaped web areas on the main spar with new plywood, complete with "skarfed" edges, sloped at a 12-1 ratio with the plywood thickness. This takes very careful work with a block plane. Wood is a wonderful material to work with.

Butt ribs needed to be totally rebuilt, a task made easy by using the old ones as templates. We used resorcinol or T-88 glue, depending on the location and fit of each joint. Both are very strong and quite resistant to moisture. When we finish, the wing will be as good or better than new in every respect.

Seeing the wing take its proper shape once again was very satisfying. Just a few more tasks and we will start the fabric-covering process.

Next page (A Mite Bit of Work: part III)

Our thanks to Dick Coffey and the Minnesota Flyer magazine, in which this article first appeared.

October 20, 2000